Liquid Knowledge

“The patient crawls to her mailbox every day.” From those eight words, written in the progress notes of a patient’s electronic health record, an entire story unfolds. In an instant, we understand that the patient can’t walk, but she’s alert enough to want her mail. We know she has no one to go to the mailbox for her, and she’s motivated to do it herself. We realize she needs more help.

That one sentence arguably gives more insight into the patient’s condition than the pages of notes, billing information, lab values and vital signs that are crammed into an electronic health record (EHR). The problem is that it is buried within all of that data. “When we bring everything forward, providers can’t tell what’s critical,” says Charlene Weir, Ph.D., professor of biomedical informatics, who uncovered the statement while studying the use of contextual information in EHRs. “Sure, you can see the whole medical record, but the meaning is completely obscured.”

The example highlights one of the great paradoxes of modern medicine. On the one hand, we haven’t captured or can’t get our hands on the vital information we need to solve patients’ complex health problems. Health care is the last sector of our economy to go digital, and most information still remains trapped in the paper filing cabinets of hospitals, doctors’ offices and research labs. Some estimate that by 2020 only half of health information will be digitized,will be locked in software systems that either can’t or refuse to talk to one another.

On the other hand, we are overwhelmed with data. By 2020, it’s predicted that we’ll have 25,000 petabytes of health data, enough to fill 500 billion four-drawer filing cabinets. From personal health records to clinical trial and genetic data to 3-D imaging and biometric sensor readings, the explosion of data has outpaced our ability to stay on top of it all. In 2010, 700,000 new articles were cataloged by the National Library of Medicine. “I’d have to read 100 published trials a day to keep up with all the new medical knowledge,” says Robert Pendleton, M.D., chief medical quality officer. The problem is that much of the data we’ve generated is unreliable, disconnected and irrelevant. Only a fraction of it is accessible, let alone actionable, at the point of care, where it could make a difference in people’s lives.

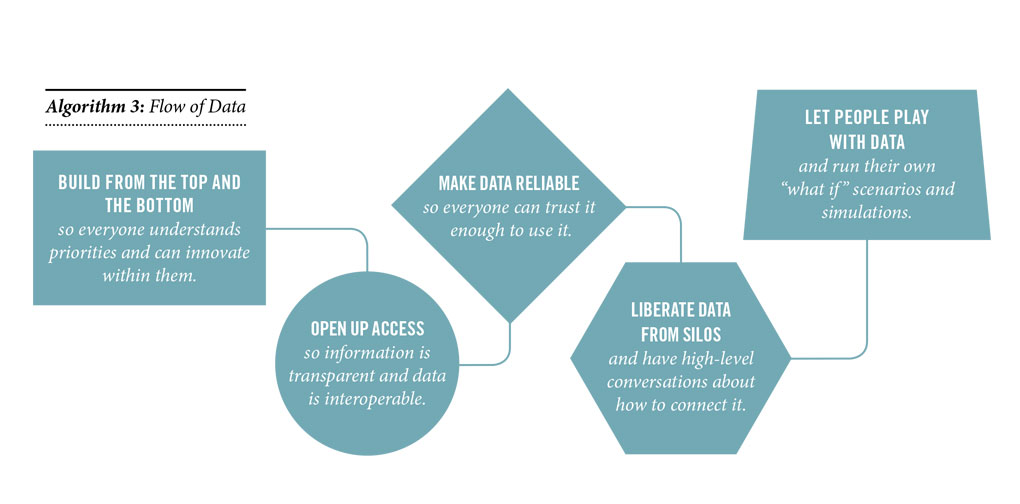

The data puzzle is the same riddle facing the entire U.S. health care system: How is it possible to have so much and so little at the same time? U.S. adults receive only half the recommended care they need, according to a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine, and yet our health system wastes billions of dollars on unnecessary tests, treatments and hospitalizations. An estimated 400,000 Americans are killed every year due to preventable medical errors. The knowledge to care for these patients exists. It’s just not being used. “We’re the only industry that knows best practices but doesn’t apply them systematically,” says informaticist Kensaku Kawamoto, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of biomedical informatics and associate chief medical information officer. There’s also a lag in translation. He points to research that shows it takes an average of 17 years following a landmark clinical study for a significant medical discovery (such as the use of beta-blockers after heart attacks) to be adopted into routine patient care. “In the flow of knowledge, there’s a real gap between what is known and what is implemented.”

REDEFINING MEANINGFUL

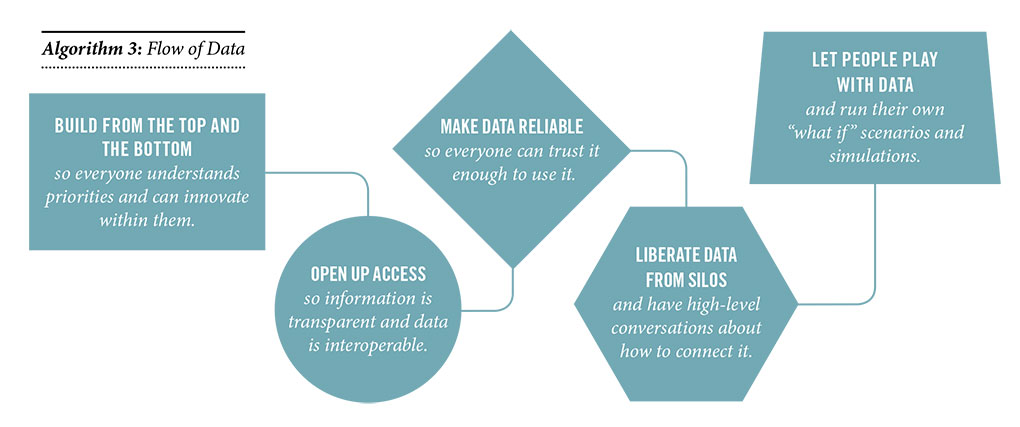

Computers and EHRs have the power to change that. Ahead is an unprecedented opportunity to standardize and revolutionize care by hardwiring knowledge into the EHR so that the computer can walk providers through best practices. “When we take knowledge and put it into a form that interacts with the computer, we take an asset and make it liquid,” says Kawamoto, who is working on a national, open-source repository of electronic clinical decision-making tools. We need to shift our thinking from pushing data to pushing knowledge. And we need to abandon the notion that implementing an EHR is the end goal, says Jonathan Nebeker, M.D., M.S., associate chief medical informatics officer for Veterans Health Administration. “Making information available isn’t the same as making it useful,” says Nebeker, who believes that Federal Meaningful Use requirements forced adoption of the EHR before it was ready. “We basically just took a paper filing system and made it electronic. We need to move to a dynamic 3-D chart that’s intuitive for providers, that gives them information useful in their daily practice and that’s easy to navigate and populate with data.” He and cognitive psychologist Charlene Weir, Ph.D., R.N., are in the throes of a complete makeover of the EHR.

Beyond improving usability of the EHR is the equally vexing challenge of interoperability. Right now the snapshots that tell the complete story of our personal health live scattered in hospital EHRs that can’t talk to one another or are squirreled away in offices of doctors whose names we might not even remember.

“When small physician practices aren’t technically or financially capable of hooking up to an EHR it hampers our ability to take care of patients,” says Chief Medical Information Officer Michael Strong, M.D. Roughly half of all hospitals and systems nationwide use EPIC as their EHR vendor and can connect through Care Everywhere. Coordinating with the other half can be difficult, especially since our system’s referral area spans five states and 10 percent of the continental U.S. Some progress is being made by giving referring providers and community hospitals access to our EHR in a “view only” manner. It’s a baby step, but of measurable value to those providers who now can access the notes, labs, radiology reports, etc., of their patients.

PUTTING DATA INTO PATIENTS’ HANDS

It doesn’t help that the public is of two minds about health data. “On the one hand, people want access to it anywhere, anytime and without a lot of barriers. On the other hand, they want all their information protected,” says Biomedical Informatics Vice Chair Julio Facelli, Ph.D., who is working on a HIPAA-compliant data sharing solution for researchers. Once people see the power of personal information to improve not just their health but to propel medicine forward, information will begin to flow more freely, he believes. Health systems, meanwhile, need to get past fears that sharing data with patients is adversarial, says Wendy Chapman, Ph.D., chair of the nation’s first biomedical informatics department. “Being open with data pushes us to be a better system. Much of the information we need to connect is out there, but it’s stuck in silos, and so are we.” Ultimately, Kawamoto says, “We need solutions that make knowledge liquid, so information can move everywhere.”