Right Mission. Right Margin.

“Whenever anyone says it’s not about the money, I grab my wallet,” quips Grant Lasson, M.B.A., associate vice president for strategy. In health care, it both is and is not about the money. “Money isn’t everything. But it is our lifeblood,” says Randall Olson, M.D., chair of ophthalmology and visual sciences. “Without it we’re dead.”

It’s complicated. That may be the most straightforward way to describe the uneasy relationship between health and money – a relationship that both defines and confuses our identity. Are we a business or a public service? Are they consumers or patients? Is it a job or a vocation? Are we here to treat sick people or keep them healthy?

To add to our identity crisis, we’ve been operating under the assumption that the more money we spend, the better care we’ll provide. We now know that’s simply not true. While spending in the U.S. is outpacing inflation and incomes, when compared to the spending of other developed nations, our overall health hasn’t kept up.

Until recently, there really was no economic imperative to fret over those issues or to change. As providers and health systems, we could afford to be duplicative and disjointed and survive – even thrive – in our patchwork system. Now with money tight and public and political scrutiny intensifying, the fragmented worlds of physicians, hospitals, payers, health systems and patients are all colliding. Our world is shifting and we need to respond. The question is how … and how quickly.

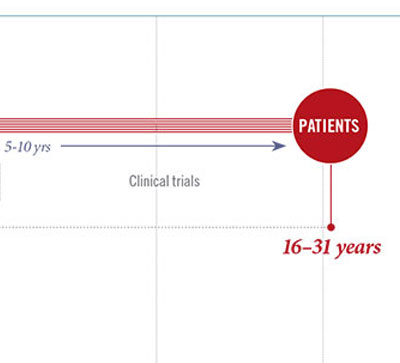

Breathtakingly fast and worrisomely slow. That’s how the pace of change feels right now. While providers and health systems feel that we’re moving at an unsustainably fast pace, payers, employers and patients are increasingly impatient.

“Fundamentally, the problem has been the misalignment of incentives,” says Senior Vice President Vivian S. Lee, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A. “Everyone in today’s fee-for-service model is paid for what they do. We’re not incentivized to do less, to work together or to prioritize and invest in what we really care about.”

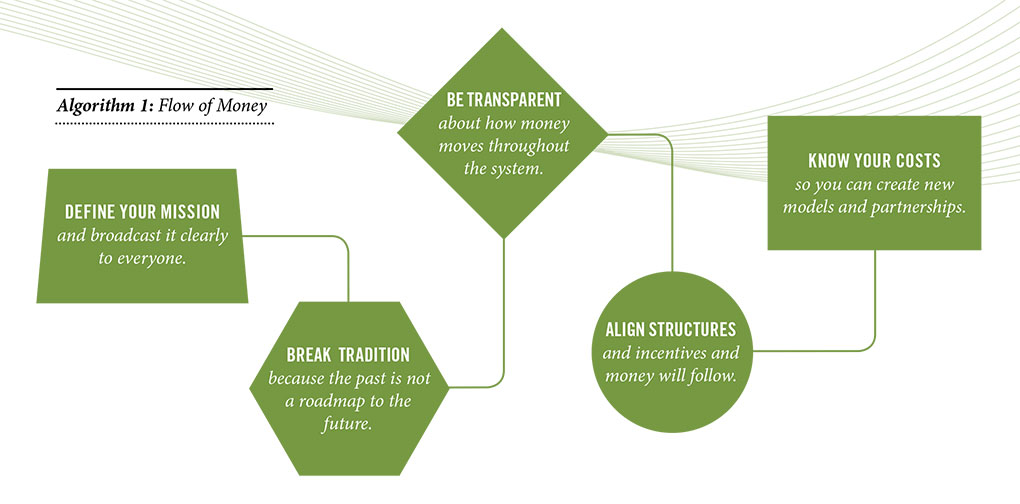

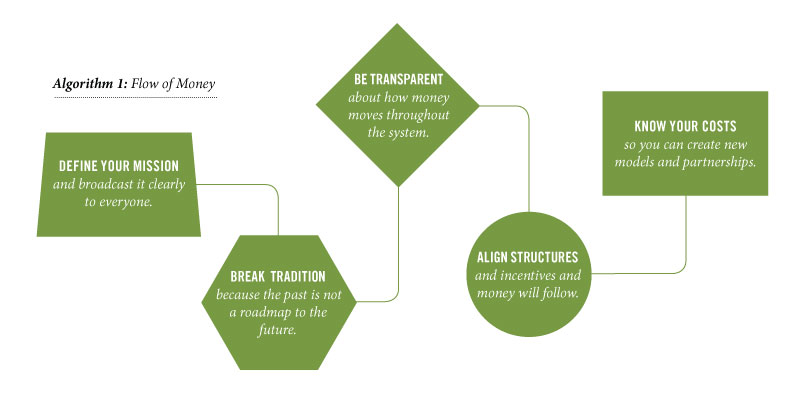

We’ve been treating the symptoms, but we haven’t yet addressed the root cause of our problems: changing the organizational and financial models we’ve held sacred, however outdated. “Money follows the structures that we’ve set up,” says Lee. In health care in general but in academic medicine, especially, those structures have made for a winding, complicated and well-hidden path of money throughout our system.

The tripartite mission is beautifully designed: patient care, research and education all symbiotically working to provide the best care and treatments for patients. But the hodgepodge of funding streams we’ve relied on to support that ideal came about haphazardly, even arbitrarily. Medicare covers a portion of what it costs to train residents, the state chips in for education, federal and private grants help fund research. But that has never been enough. The gaps to fund buildings, technology, researchers and students has been filled by the generosity of donors and revenue from the clinical enterprise.

When the economy was strong and business was good, we didn’t have to be too particular about how exactly that was all happening. But in this constrained economy, those funding streams are drying up. Now it’s critical for us to be clear about not only how money is flowing throughout our system but what good it’s doing. “We’re starting to measure value in the clinical enterprise, but we have a long way to go to figure out how the money were spending affects the quality of education and research,” says Lee. It’s the old business maxim: you can’t manage what you don’t measure. And frankly, we haven’t been measuring.

Building a new pipeline that’s sustainable, realistic and aligned around a singular purpose will take buy-in from everyone. “Everything is derivative of alignment,” says Chief Financial Officer David Browdy, M.B.A. To start the process, we hosted a retreat this past spring and invited the chairs of our 22 basic science and clinical departments, the deans of five schools and colleges and a handful of leaders from the hospitals and medical group. The fundamental questions we explored were: Who are we? And how do we want to move forward?

Harvard business strategist Michael Porter, Ph.D., M.B.A., says, “Sound strategy starts with having the right goal.” Out of that retreat, we determined that our goal, our mission, is to advance health. Everything we do – discovery, education and clinical care – will focus on taking care of the health and well-being of the population we serve, not just during episodes of care but throughout their lifetime.

“In our current system, the best strategy for our cardiovascular service line is to sell cigarettes, not prevent disease,” says Chair of Surgery Sam Finlayson, M.D., M.P.H. “I want to be paid to keep people healthy, not just to treat them when they’re sick.”

Chair of Internal Medicine John Hoidal, M.D., agrees. “I want to see medicine operate where the patient always comes first, and that our commitment is to their health and well-being. When we’re driven by a social desire to help the population, everything flows from there.”

It’s no small feat to get a room full of dedicated leaders to agree, but it’s a different thing altogether to change an entire culture, especially when the future is so uncertain. “It’s really hard to go from something we know to something we don’t,” says Browdy, when asked what keeps him up at night. “We have an entire system and lots of smart people within it who need to change.”

Darrell Kirch, M.D., president and CEO of the Association of American Medical Colleges, recently said about change: “It’s almost as if you have to mount a campaign to win the hearts and minds of people.”

One mission. One system. How that looks, what that means, how we change is still unfolding. One thing we know for sure: What we’ve done in the past will not take us to where we need – and want – to go. “We need a whole new vision,” says Lee. “And organizations like ours are the ones that can come up with the good ideas and innovative solutions.”