Community HealthWho's Responsible?

No doubt, we’re starting to recognize that health is a mishmash of factors that extend way beyond our health care comfort zone. Now our challenge is how to stretch our imaginations, work together and trust one another, so we can be there for individuals and populations when and where they need us.

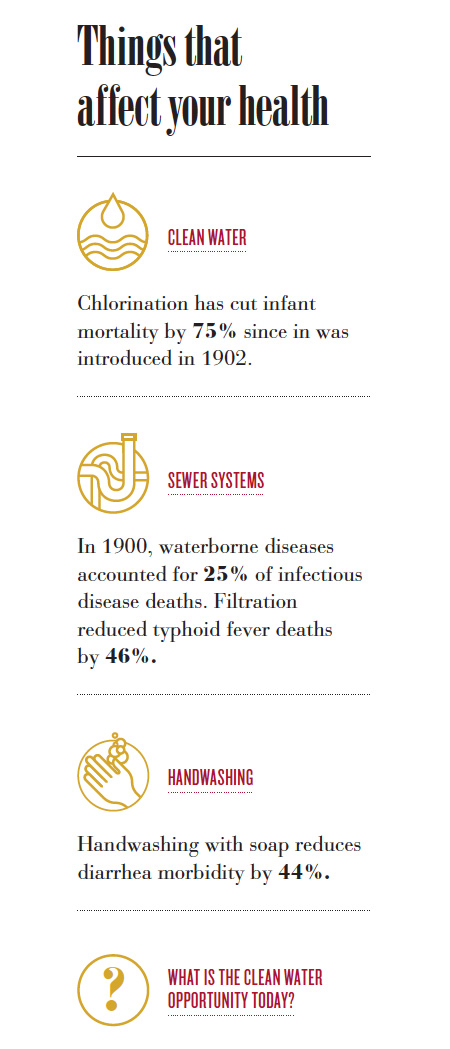

We’ve vaccinated billions of babies, invented penicillin, developed an artificial heart and mapped the human genome. But the most significant advancement of public health over the past 200 years was a government infrastructure project— diverting sewage and wastewater away from drinking water sources and chlorinating and filtering the water coming out of the tap. Clean water has cut overall mortality in major cities in half and infant deaths by three-fourths.

If the most important global health accomplishment ever achieved was through water pipes, where should we be focusing our efforts today? If we know that our health care delivery system influences only a small percentage of overall health, what should we be doing? Making sure our patients have clean water (think: Flint, Michigan) and good schools and fresh vegetables and convenient transportation and adequate housing and a living wage? Should the bulk of our efforts be focused on stopping smoking, conquering obesity, ending addiction, addressing mental health and tackling poverty?

Truly taking care of the community —addressing all of the social determinants of health—is perhaps the most disruptive idea that’s ever been posed to our health care system. It’s also the next step, especially for academic medical centers (AMCs). Unlike for-profit hospitals and health systems, which are primarily accountable to their shareholders, we are ultimately accountable to our communities. “We’ve got to stop thinking of ourselves as the crown jewel of the community and get back to thinking of ourselves as who we really are—a public servant,” suggests Darrell Kirch, M.D., president and CEO of the Association of American Medical Colleges.

What we’ve come to realize—and admittedly, it has taken us a while— is that health care alone cannot take care of communities. Health happens at the intersection of individuals, families, employers, pastors, teachers, philanthropists, politicians, health care providers, and countless community workers and nonprofits. But the question remains: Who’s responsible for making those critical connections? Who’s in charge? And who’s going to pay for it? That’s not how we’ve organized ourselves. That’s not what we’ve trained for. And, that’s not how we’re getting paid.

“Is population health a business model that can stand on its own? Probably not,” says Gordon Crabtree, M.B.A., interim CEO of Hospitals and Clinics. “Under any scenario, the work of population health takes a lot of time and energy from our providers and systems.” But Crabtree notes academic medical centers have been doing this kind of work for years. AMCs long have supported money-losing services that are vital to their communities and provide a safety net, taking care of the uninsured, prisoners, the homeless. For University of Utah Health, that tallies up to more than $100+ million in charity care annually. But Crabtree admits the work that we’re doing already may be just the tip of the iceberg of what needs to be done. And our scope of responsibility for health may still be too narrow.

First, Do No Harm

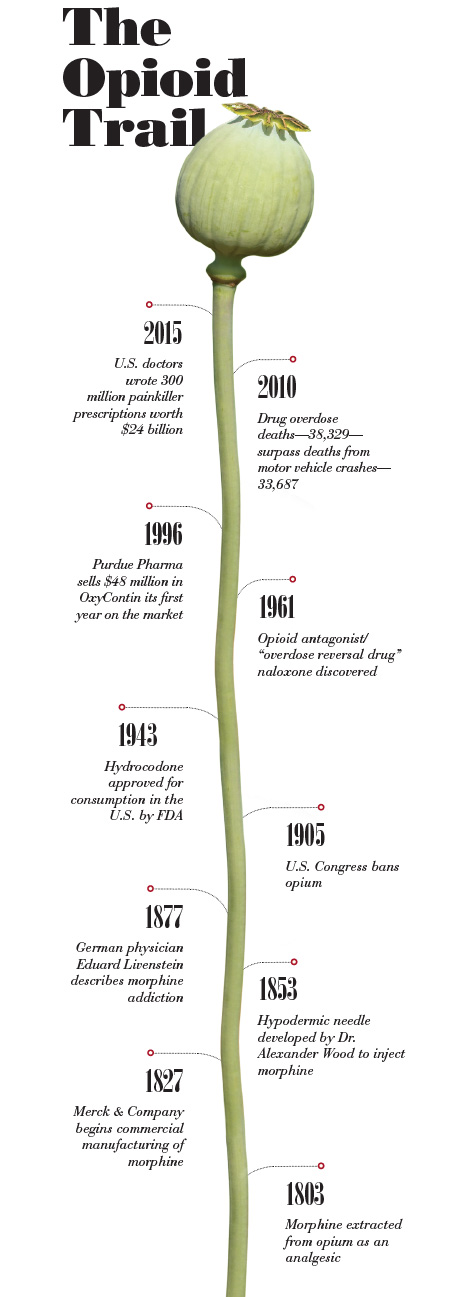

In most cases we’ve done too little. In some cases, however, we’ve done too much. In 1986, the World Health Organization called for the limited use of morphine as a responsible way to manage cancer pain— “the right drug in the right dose at the right intervals.” The drug was so effective, doctors started using morphine and other opioids to treat a variety of pains—wisdom teeth, kidney stones and knee replacements, to name a few.

Then, in the 1990s, the American Medical Association classified pain as the “fifth vital sign.” Adding to the pressure to keep patients comfortable, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) included three questions about pain in its Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey starting in 2006. “Out of a compassionate call to action, opioids got applied to lots of different situations,” says Scott Junkins, M.D., medical director of the Pain Management Center. “The problem was that we didn’t have good research to show what the next step with these powerful drugs should be.” In the absence of data, and with pharma promoting opioids’ miracle powers of pain management, doctors prescribed.

We’ve been trying to manage the fallout ever since. Sales of prescription pain pills have skyrocketed, increasing four-fold from 1999 to 2010. But hospitals and health care systems also made money during the opiate boom. A Wall Street Journal review of painkiller prices at California hospitals in 2004 found prices charged for a single, $1.35 Percocet pill ranged from $6.50 to $35.50.

It’s the cost to society, however, that has been the steepest. The nationwide opioid epidemic results in tragically high overdose rates and related spikes in hepatitis C infections from intravenous heroin use.

Opioid addiction doesn’t discriminate. It’s insinuated its way into nearly every community—high and low-income, black and white, religious and agnostic, homeless youth and suburban housewives—making a mockery out of traditional stereotypes about addicts. “It’s everyone,” says pediatrician Karen Buchi, M.D., chair of U of U Health’s opioid task force. “It’s the woman sitting next to you in church and the man sleeping under the tree in the park.” Utah is not immune. The state has some of the highest opioid prescription rates in the country and the fourth-highest per capita overdose rate in the nation. Six people die each week in Utah.

Dealing with drug-seeking patients is one of the top two stressors for physicians, says Susan Terry, M.D., community physician group executive medical director. “Doctors end up having a crucial conversation every 20 minutes, all day long,” Terry says. It’s estimated that 36 percent of all ED patients are seeking drugs. Discerning who’s really in pain and who’s a drug seeker is exhausting, demoralizing and risky. Getting it wrong can be catastrophic. Every opioid prescription is tracked by the state, and doctors who write scripts for known drug seekers could lose their licenses.

The solution comes down to education and support—for both patients and providers. University of Utah Community Physician Group adopted opiate prescribing guidelines in 2015 and embedded a nurse practitioner to help patients manage their pain with medication and other means—mindfulness activities such as meditation, therapeutic massage and physical therapy. In the first seven months of 2016, prescriptions for the 17 opiate drugs that are internally tracked were cut in half.

An interdisciplinary model and alternative pain treatments—such as electrical spinal stimulation and dry needling—also have worked at the pain clinic Junkins manages. Over 30 years, the center has grown from one doctor with a bed and a curtain to eight treatment rooms and nine attending physicians managing 11,000 patient visits last year. “Pain is multi-faceted and we have a long way to go to address it,” says David Anisman, M.D., associate medical director of Community Physician Group. “Not every treatment for pain is appropriate for every person. We have to ask, ‘How well can you function with this level of pain?’ Having zero pain may not be an option.”

Who’s responsible for letting the opioid genie out of the bottle? It depends on whom you ask. But it will take all of us—physicians, pharmaceutical companies, nonprofits and politicians—working together to shove it back in.

Flipping the Top-Down Approach

Making tamale dough—the moist, succulent kind that falls out of its corn husk without crumbling— starts with whipping two-thirds of a cup of lard and a bit of broth. That’s how it should be done. That’s how the women in community health worker Jeannette Villalta’s wellness group did it. So when Villalta became a health coach as part of a five-year study targeted at reducing obesity among women in health disparity groups, she knew where Latinas needed to focus—food. “Food is part of the culture,” Villalta says. “We had to learn about healthy substitutes, like plain yogurt for sour cream, eggplant for lasagna noodles, olive oil for lard. It was educational—even for us as wellness coaches.”

With about one in three Americans classified as obese by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the health care and business costs of being overweight are mounting. For individuals, that means higher out-of-pocket health care costs, potential lost days at work and diminishing long-term health. “This message is much stronger when coming from the members of the community, as well as nutritionists and doctors,” says Louisa Stark, Ph.D., research professor of human genetics. Studies estimate that just 20 percent of health behaviors can be changed in the clinic alone.

To reach out to health disparity groups, Sara Simonsen, Ph.D., associate professor of nursing, and Kathleen Digre, M.D., professor of neurology, asked community leaders to help design an obesity intervention study. Community Faces of Utah identified 500 underserved women in five ethnic groups—African-Americans, African immigrants, Latinas, American Indians and Pacific Islanders. After a three-month wellness training program, coaches were able to navigate cultural sensitivities around weight and exercise. For example, Pacific Islander coaches were able to gently push past long-standing cultural notions of weight being a sign of wealth and leisure time. For African women from Rwanda, Burundi and Congo, who wear loose, wrapped robes called “igitenge,” tight exercise wear was a stumbling block. So coaches helped incorporate West African dances into an exercise program. The coaches developed relationships with the participants that went far beyond taking their blood pressure or measuring their waistlines. And that was key, says Simonsen.

Crowdsourcing Population Health

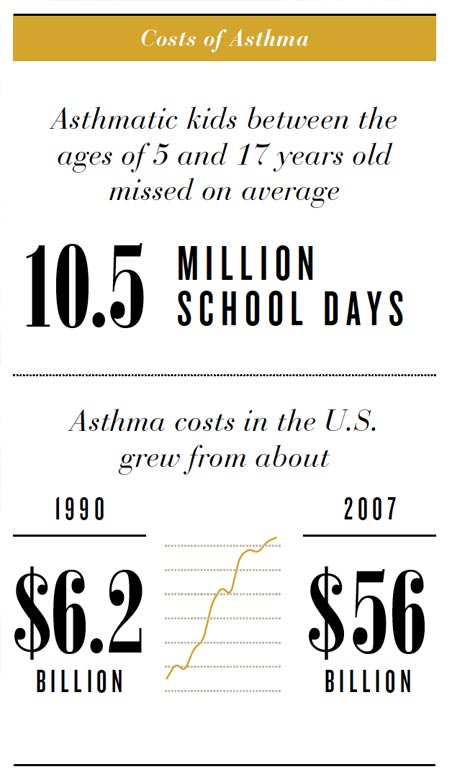

Asthma doesn’t happen in a doctor’s office. It’s triggered at school, at home, in the car and at play. So a population health solution for pediatric asthma probably won’t be found in a clinic either. Almost as soon as she was a mom, Jordan Gaddis was the mom of a kid with asthma. By the time her son Graham was one year old, he’d had two bouts with RSV. He’d been on oxygen 24 hours a day and in the hospital for days on end. She’d sneak into his room to try to slip a blood-oxygen monitor on his toe while he slept. The first years of Graham’s life are a blur of sleepless nights and rounds through the children’s hospital and pediatrician’s office.

Graham is one of an estimated 6.3 million kids across the country who have asthma, according to the CDC. For minority populations, the statistics are even more dire: Asthma rates among African-American children jumped 50 percent from 2001 to 2009, and those children are five times more likely to die from the disease than their white classmates.

The problem has been figuring out which trigger set off a child’s asthma attack and sent a family to the emergency room. “What we’re trying to do is better understand the complex role that exposure to environmental asthma triggers play in childhood asthma,” says Flory Nkoy, M.D., M.S., M.P.H., associate research professor of pediatrics. “You can’t control it well if you don’t know what exacerbates it.”

Using a $5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, Nkoy and a team of engineers, biomedical informaticists and pediatricians developed a sensor-based online tool for tracking pediatric asthma. Families will be able to monitor the indoor and outdoor environmental factors their kids are exposed to and, eventually, pinpoint which one triggered that trip to the emergency room or boost in medication.

Small enough to tuck into a kid’s backpack or attach to an armband like an iPod, new high-tech sensors can track particular pollutants, distinguishing between car exhaust, pollen and the aerosol the janitor uses to clean school lockers. At the end of the day, parents can upload the data into a minute-by-minute snapshot of the kinds of things a kid has been exposed to and report any related symptoms or visits to the doctor or hospital.

“This project will make precise, personalized data available to researchers so we can see in near-real time what’s happening to people,” says associate professor of nursing informatics Kathy Sward, Ph.D., M.S., R.N.

“We’ll finally be using the same big-data techniques that retailers collect from consumers every day, but we’ll be applying them to a child’s health,” says Julio Facelli, Ph.D., associate director of the Utah Center for Clinical and Translational Science. The system, he says, will allow researchers “to answer questions they didn’t even know they could ask.”

Next Steps

For now, population health innovations are outpacing payment models. Naloxone kits are not reimbursable in our current health care system. Individual asthma sensors may not be covered by a patient’s insurance plan. Do we make changes anyway, simply because they’re the right thing to do? Department of Surgery Chair Sam Finlayson, M.D., M.P.H., says yes. “Whether we like it or not, we’re all in this together. People’s health affects other people,” he says. “We’re all paying for health care. We all pay taxes. We’re all paying health premiums. We have a societal obligation to provide high-value care. And we also have a responsibility to the larger whole to preserve our health as a community.”