TRANSPARENCY: WILL IT HELP OR HARM HEALTH CARE?

Transparency is a noble quality. We like people who are open and honest, so it makes sense that we yearn for those same virtues in health providers and institutions. But transparency is a double-edged tool. Responsible transparency can build trust just as quickly as reckless transparency can erode it. It can be used to teach us something important about ourselves or to punish and shame. Doing it right takes time, money and a careful weighing of competing priorities—a complicated, and time-sensitive, calculus for today’s health organizations.

“Google me,” said Courtney Scaife, M.D., as she walked into the office of Chief Medical Officer Thomas Miller, M.D. He did and up popped an ugly comment about the pancreatic cancer surgeon. How long had it been floating around on the Internet? Was it even a former patient? A disgruntled co-worker? “Now look at these comments,” she said, placing a stack of Press Ganey patient survey results on his desk.

Scaife has a tough job. The five-year survival rate for patients with pancreatic cancer is 6 percent. Most of her patients are dying, yet they fill their surveys with overwhelmingly positive and appreciative comments about the care she provides. “You privately email these comments to me every month, but that’s not what my patients see when they Google me,” an impatient Scaife told Miller. “You have a website. You have my bio. Why don’t you put these reviews online?”

There was no denying Scaife’s logic. “We have reams of unbiased, accurate data that we know is from actual patients, and most of it is very positive,” says Miller. “Why keep this feedback so private? Why not share it?”

“EVERYONE WANTS TRANSPARENCY TO BE A TRICK. IT’S NOT A TRICK. TRANSPARENCY DOESN’T START FROM THE OUTSIDE. IT STARTS FROM WITHIN AN ORGANIZATION WHEN WE LOOK TO EACH OTHER AND LEARN FROM EACH OTHER. THAT’S HOW CHANGE HAPPENS.”

Vivian S. Lee, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A., Senior Vice PresidentScaife had hit on a fundamental problem in health care: Information asymmetry. We collect terabytes of data and keep most of it behind a firewall, sometimes not even sharing it internally, for reasons that often have nothing to do with delivering care. And the American public—in most ways, incredibly demanding consumers—has shown uncharacteristic patience with the lack of information.

It’s not that we don’t want to find good doctors and safe hospitals. We’ve just accepted that we’ll have to rely on the advice of friends and family—even perfect strangers if they have reasonable suggestions. “It’s kind of shocking,” says Robert Pendleton, M.D., chief medical quality officer. “We spend more time vetting a new car or TV than a doctor or hospital.”

Consumerism, though, is on the march and so are out-of-pocket expenses, prompting patients to take a more active role in their health. No longer satisfied playing the role of acquiescent patient next to the paternalistic physician, they’re increasingly empowered, informed by Dr. Google and asking tough questions, such as: Where is the best, safest place to get this procedure, and is it worth the risks and expense? Proponents see the rise of consumerism as a powerful means to make health care better and more affordable. What’s missing is what’s always been missing: Access to the information patients need to participate as equal partners in their health care.

The Problem with Rankings

More data isn’t the answer. Consumers need reliable data organized in a meaningful way to guide their choice of doctors, hospitals and health plans. Trouble is, most of the information available today is incomplete, incomprehensible or designed to expose bad actors, which paints a distorted picture of the profession, causing patients to distrust physicians and physicians to feel under attack. “In our own experience with posting data online, we’ve really tried to reduce that level of pain, because it shouldn’t be an adversarial relationship between patients and providers. It should be a partnership,” says Senior Vice President Vivian Lee, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A.

Want to find the best hospital? There are plenty of report cards out there catering to our appetite for easy-to-digest rankings and lists, but don’t expect to find any consensus. A study in Health Affairs revealed no single hospital receives high marks from all four of the most popular rating services: U.S. News & World Report, The Leapfrog Group, Healthgrades and Consumer Reports. The very same 27 hospitals that were rated “best” by one group were rated among the “worst” by another ranking.

Federal data dumps comparing the cost (average charges) and safety of hospital procedures bring some consistency and objectivity to the scoring. But, assuming you have the patience to download the information into a massive spreadsheet, good luck making sense of it. “The challenge is putting data into a format that’s useful, and not having people shrugging their shoulders. It falls to all of us to try to make sure that doesn’t happen. Because it’s too important,” says Charles Ornstein, an investigative journalist for the nonprofit ProPublica. “We want to make sure our data has as much context as possible and is as helpful as possible.”

The online tools are getting sharper, thanks in part to Ornstein and his ProPublica colleagues, who recently launched a Surgeon Scorecard that shows how surgeons performing eight elective procedures compare on safety using Medicare death and complication rates. ProPublica’s methodology has been praised by patient safety experts and criticized by some providers who question the scorecard’s reliance on readmission rates as a proxy for skill. Should a hip surgeon be held wholly responsible for such complications as constipation or deep venous thrombus? But no metric is perfect. “Recognizing that all of these methods have advantages and disadvantages, progress will be iterative and incremental,” opined David Classen, M.D., adjunct associate professor of internal medicine, in a review posted on ProPublica’s website.

Pendleton agrees: “It will get better over the next five to 10 years. But for now, most health decisions will still be made based on the kind of insurance one has, convenience and word of mouth.”

Enter the Crowd

Fortunately, “word of mouth” is no longer limited to friends and family. We now have the Internet, or the crowd, to rely on. Online reviews are like “Ask Martha” on steroids, bringing an exponential “n” factor to the discussion. In one month in 2015, the three doctor review sites, HealthGrades, Vitals and ZocDoc logged more than 10 million unique visitors. The problem with these third-party sites is that their sample size is small (two studies found an average of two and three reviews per doctor), and there’s no way to verify that the reviews are from actual patients and not a family member, competitor or paid promoter. Recognizing this weakness, Yelp and ProPublica teamed up to augment consumer reviews with verifiable survey data from Medicare—a crowd-meets-data combination that could be a game-changer.

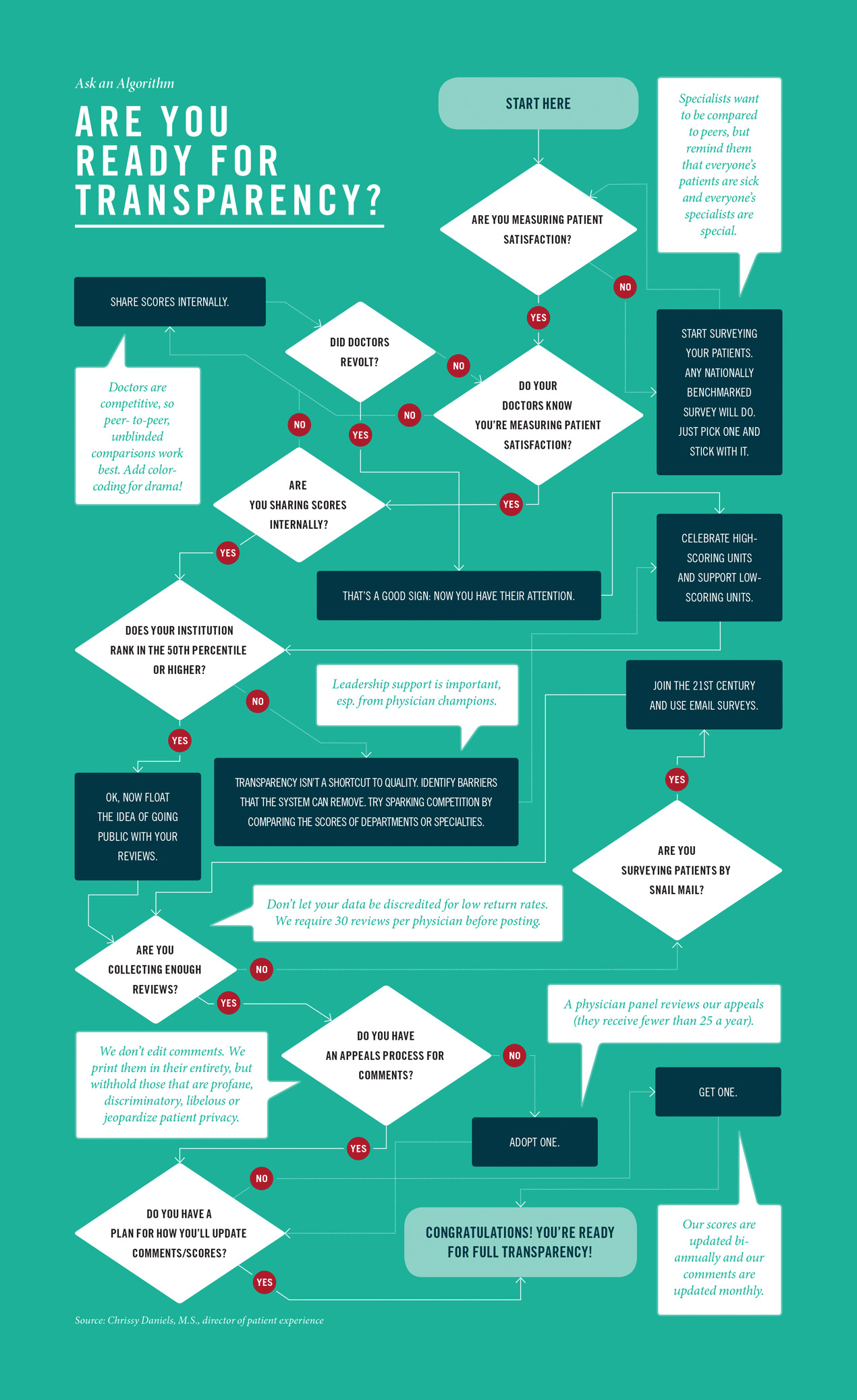

But the question remains: Why sit back and let Yelp, ProPublica and HealthGrades take the lead and define our online reputation for us? That’s what Miller wondered as he weighed the pros and cons of putting the University of Utah’s physician reviews online. It was the right thing to do, and the smart thing to do. Of that, Miller was confident. But the University would be forging new territory—no other academic medical center had gone public with its data from Press Ganey, a processor of patient satisfaction surveys for about half the nation’s hospitals. Miller knew physicians would be unsettled, and in fact, their objections were numerous.

Won’t this be bad for business when none of our competitors are making this information public? In trying to avoid negative reviews, won’t providers be encouraged to bend to the unreasonable demands of patients who are unqualified to judge the quality of care? And won’t this, in turn, lead to over-testing, over-treatment and higher costs? Why should we be on the bleeding edge of something so risky and untested?

But believing “the best defense is a strong offense,” Miller persisted in championing the idea to his physician colleagues. And on Dec. 1, 2012, after six months of spirited debate and countless meetings, the online reviews went live—posted, as Scaife had suggested, on the institution’s Find-A-Doctor website with unedited comments and an accessible five-star ranking. “I’m glad it worked, but it was a very rocky road,” says Chrissy Daniels, M.S., director of patient experience. “I see my job as trying to make physician practices more satisfying and to be a support to them, and this felt like it put us at odds with them. We presumed no harm would come but there’s always a risk. I worried, ‘What if this doesn’t work?’”

A Dose of Trust

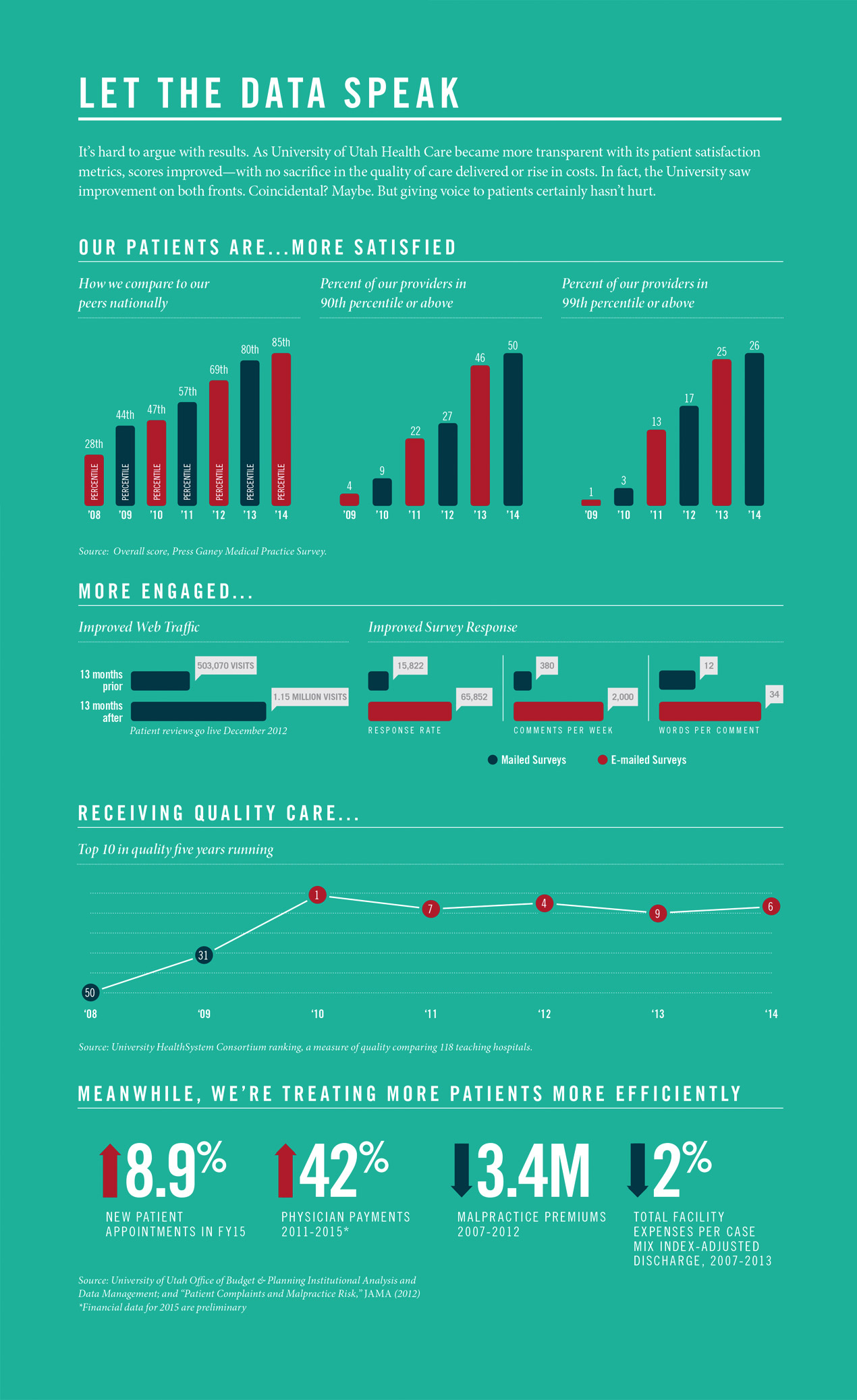

Looking back now, it’s tempting to paint the experience as proof of the miraculous, transformative power of transparency. Once in the 28th percentile nationally for patient satisfaction, we now rank in the 85th percentile. One of every two of our physicians are in the top 10 percent when compared with their Press Ganey peers, and one in four physicians place in the top 1 percent nationwide. And we achieved these gains with no sacrifice in quality or rise in costs. But transparency is no panacea. Embracing it takes a heavy dose of trust—trust in each other, trust in the organization and trust that what’s about to happen is, in fact, in the best interest of patients. And that kind of trust isn’t built overnight. “Everyone wants transparency to be a trick. It’s not a trick,” says Lee. “Transparency doesn’t start from the outside. It starts from within an organization when we look to each other and learn from each other. That’s how change happens.” Online reviews may have been the accelerant, but the groundwork for improvement was meticulously laid over seven years. “It was the result of a ton of spadework to engage provider teams and align the organization around a shared purpose and shared set of goals,” Daniels says. And that spadework began in 2008 at a leadership retreat organized by Lee’s predecessor, Lorris Betz, M.D., Ph.D.

Giving Patients a Voice

Over the years, the University had earned a reputation as the regional center for cutting-edge, high-end specialty care. But service took a back seat to the pursuit of clinical excellence. Betz was unhappy with the feedback he was receiving from unsatisfied patients, including his wife, Ann. So he summoned the chairs, deans and hospital leadership to his home, where he read aloud excerpts from patient complaints about long wait times, delays in scheduling appointments, poor communication and an overall lack of professionalism. “It was the perfect storm of embarrassment and frustration that created the urgency to change,” says Betz, who ended the retreat with an uncharacteristically stern mandate to create an “exceptional experience” for every patient at every point within the system.

The former vice president’s mantra—“medical care can only be truly great if the patient thinks it is”—fundamentally changed the paradigm by making the patient, not the physician, the arbiter of good care. “It’s important for organizations to understand what they’re aspiring to be. Our problem wasn’t just in some processes. It was about who we thought we were,” says Sean Mulvihill, M.D., CEO of University of Utah Medical Group.

With a goal in sight, the next step was to find the right way to measure progress. Metrics matter. The University chose to use nationally benchmarked Press Ganey data, bringing consistency and credibility to the scoring, and took great care in deciding how to survey patients, focusing on questions related to professionalism, communication and shared decision-making. “We specifically did not ask, ‘Did your physician do whatever you asked for?’” Daniels says.

But for physicians it was still a huge shift. The metrics didn’t jibe with how they defined quality. For every study linking satisfied patients with good clinical outcomes and patient safety, there was one showing how patient satisfaction didn’t matter and would make quality worse and push costs higher. “What physicians think the patient wants is for them to think clearly, draw on their knowledge, make an accurate diagnosis, and if there’s surgery, operate with skill,” says President of Medical Staff Blake Hamilton, M.D. “So it creates a disconnect. When they receive surveys back they’re thinking, ‘I just saved someone’s life and I’m being docked because I wasn’t nice enough in the follow-up visit?’”

Doctors have pride of ownership over their practices, but they don’t deliver care on their own. “The patient experience is everyone’s responsibility, which is why we were very clear that these metrics would never be used in a punitive manner,” Miller says. To further reassure and support physicians, the hospital took responsibility for things it could control, implementing system-wide changes, such as offering valet parking (no tips allowed). An on-call “patient ambassador” was hired to cater to patients’ non-medical needs, such as fixing broken bed alarms. “All of our care teams wanted to be part of the solution. The first scores to improve were ‘courtesy of the receptionists and medical assistants,’” says David Entwistle, M.H.A., CEO of University of Utah Hospitals and Clinics. “When you call upon people to do the right thing, they respond.”

Coaching Notes

But if physicians no longer objected to the metrics, they didn’t really pay attention to them until 2011 when the University shifted from paper surveys to emailed questionnaires, driving up the response rate by nearly 400 percent overnight. The feedback with email surveys was more timely (seven days old) and more detailed. “With written comments, you’d get, ‘It was great. He was nice. The check-in process was smooth,’” says Daniels. But with e-surveys there was no more mind-reading about what patients meant by a score of three or four, because they explained exactly what they meant. “We got little coaching notes,” says Daniels. Patients gave tips suggesting that the physician needed to have more eye contact, or that the exam room needed an extra chair for family members or that the doctor “was very knowledgeable, but could work on being more personable.” Suddenly, hospital administration was no longer the middleman—patients were talking directly to physicians and telling them what they wanted.

Thomas Miller, M.D.

Chief Medical Officer

One by one, department chairs started sharing data with their faculty. At first the comparisons were blinded so faculty members could see how they performed in comparison to their peers but there were no names attached. “Guess what?” says Daniels. “No one paid attention.” But then the department chairs unblinded the data so everyone could see everyone else’s patient satisfaction scores—your name in green if you scored higher than the goal and in red if you didn’t. “This was the most emotional work we did. There was a lot of heartache and grief around this time,” says Daniels.

There are two reasons to embrace transparency, according to Pendleton: “To give patients more information and to encourage providers to change behavior.” After unblinding the scores, patient satisfaction scores jumped from the 28th to the 50th percentile. “Doctors are competitive and most want to do the right thing. It’s sometimes the busyness of health care that gets in the way,” says William Dunson Jr., M.D., director of Huntsman Cancer Institute’s Acute Care Clinic and Internal Medicine Service. “When confronted with data, physicians have two options. They can either ignore it or they can own it and, if needed, make changes to improve. Most of our faculty intuitively chose the latter,” says Robert Glasgow, M.D., chief value officer for the Department of Surgery. When Lee arrived in 2012, she took transparency a step further and began sharing scores by specialty at leadership meetings with department chairs. “That grabbed the attention of the remaining few departments that we’d struggled to engage for years,” says Daniels.

Patient reviews brought science to the art of bedside manner, showing through data why it’s important to knock and pause before entering the exam room, to be respectful and to make eye contact. “Patients want the best care they can get, but they also want their emotional needs met,” says Dunson, who has been a tireless champion of patient satisfaction at Huntsman Cancer Hospital, which has all of its clinics rated in the 99th percentile nationally. “Having their responses fed right back to you . . . It re-centers you, and reminds you of why you got into this career in the first place.”

The Final Push

By the time the University was contemplating going fully public with its scores, physicians averaged 4.7 out of 5 stars. Still, it took Miller and Daniels going door-to-door to assuage individual concerns by pointing out how Press Ganey scores compared to those already being published on sites like HealthGrades. “It was a small minority who persisted in opposing it, but they pushed back pretty vigorously,” Miller says.

Some feared one or two negative comments would sink their practice. And they worried that only the most disgruntled or the most pleased would post reviews, skewing the data. To counter that, University of Utah decided to only publish the reviews of doctors who have worked six months within the system and accumulated at least 30 surveys. That’s far more than found on other “shop-a-doc” sites, making it ring truer for consumers, who are adept at sifting through and weighing the opinions they read.

Also, there would be no editing of comments. “The public is not foolish, they are going to be distrustful if there is not a spectrum of comments,” says Miller, who simply sees the negative comments as an opportunity to improve—“we want to be held accountable.” And, as for the positive comments? “They’re far more effective and affordable than advertising,” says Miller.

A year after reviews went live, traffic to physician profiles had more than doubled. “Any digital marketing strategist would kill for that kind of growth,” says Brian Gresh, M.P.A., former senior director for Interactive Marketing and Web. Not all of that growth can be directly attributed, Gresh says, but it certainly played an important role. It also improved search position. Studies estimate that one-third of all web traffic comes from the first result and now the University owns that top spot. Meanwhile, satisfaction scores continued to rise.

For providers like Scaife—whose scores rank in the high 90th percentiles—it’s about accuracy. Now when prospective patients Google her, they can be sure they are hearing from actual patients. Consumer feedback hasn’t resulted in wholesale changes to her practice, but it has reinforced certain things. “I always draw out the anatomy of the surgery I’m going to perform,” says Scaife. “And even though we all feel a lot of pressure to be more efficient, that is something I will never get rid of because I know from the comments how much patients appreciate it.”

A lot of patient satisfaction is about managing expectations and the ratings and comments accomplish that too. The patient knows beforehand that she might have to wait longer, or that the nurse is really the fountain of information. “Patients certainly look at the reviews and vote with their feet,” says Glasgow. “I get comments a few times a week saying, ‘I read about you.’ That feels good.”

Other health centers have started going public with their reviews, including, Stanford University, Wake Forest Baptist Health in North Carolina, Cleveland Clinic and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Daniels has talked to more than a dozen organizations about how they can put their reviews online. “We’re entering a marketplace driven by competition. And it’s competition on the right things, not on who’s got the best brand,” says Thomas Lee, M.D., Press Ganey’s chief medical officer. “It’s competing on who can actually meet patients’ needs and do it as efficiently as possible. It’s really value.”

What's Next?

“Five-star” care is now ingrained in our culture, and opening the way to even greater levels of transparency. It’s giving patients a voice, and in so doing, shifting the paradigm for how we deliver and gauge the quality of care. We’re moving more of our specialists off campus into conveniently located neighborhood clinics that stay open after hours and on weekends. Some clinics even do house calls and deliver same-day mammography results. We’ve launched an online scheduling pilot, allowing patients to schedule appointments the same way that they book hotels and flights. And, following years of internal transparency of our costs (see Lifting the Veil, page 32), we plan to publish prices for hundreds of our procedures. Ten years ago, we might have written off these improvements as impossible or impractical. But now they’re happening with increasing speed, because it’s what patients want and we’re finally listening. The hard part is past us. In fact, when we asked one of our division chiefs what he thought about going public with more of our data he said: “Do whatever you want. You’re already putting what my patients say about me online for all the world to see.”

The next step is to marry our cost data with quality metrics—specifically, metrics matched to the individual health goals of patients. “The outcomes that matter most to patients are the outcomes that matter most,” says Orthopaedics Chair Charles Saltzman, M.D., who spearheaded an initiative where every orthopedic patient is given an iPad at check-in and asked to answer questions about how they are feeling and functioning. The information helps doctors understand patients’ needs and tailor treatment accordingly. Eventually, it will enable providers to more precisely predict what different patients—a 23-year-old athlete versus a 67-year-old retiree—should expect to gain from treatment. By 2016, one-third of the University’s outpatient units will use Saltzman’s model.

“Like all health systems we’re experimenting and we still have a long way to go,” says Lee. “What we’ve found, though, is that with the right patient-centered vision, the right data and the right teams, change is possible. Transparency is vital to that process, but it’s just one of the levers driving improvement—not an end goal in and of itself.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Online Physician Reviews: The Method to Our Madness

Health organizations understandably have reservations about putting their physician reviews online. There are, of course, no guarantees, or surefire recipes for success. We’re all experimenting. In the spirit of transparency, here are answers to some of our most frequently asked questions.

WHICH PROVIDERS ARE INCLUDED IN ONLINE SCORES?

Providers are evaluated on their outpatient clinic visits. For statistical reasons, providers must have 30 surveys returned in 12 months.

HOW DO YOU CALCULATE THE STARS?

We take the mean score and divide it by 20, which corresponds to the five-star Likert scale used by other rating websites, such as HealthGrades.

HOW DO YOU PROMOTE THE SURVEYS TO PATIENTS?

We send an email to patients three days following their visit, with a reminder sent two days later.

DO DOCTORS SEE THE COMMENTS BEFORE POSTING?

Yes. We pull comments every week, and send them to unit managers (and any provider who asks for them). They have 14 days to flag comments of concern.

DO YOU EXCLUDE ANY COMMENTS?

Yes. We exclude comments for profanity or language that is discriminatory, libelous or risks patient privacy. We do not edit comments. All comments are posted in their entirety.

IS THERE AN APPEALS PROCESS?

Comments of concern are sequestered until they are reviewed and adjudicated by a panel of physicians. We receive very few appeals.

HOW OFTEN DO YOU UPDATE RATINGS?

Five-star ratings are updated two times a year. Comments are updated monthly and posted for at least 12 months.

HOW DID YOU COLLECT PATIENT EMAIL ADDRESSES?

We engaged registration staff and offered awards to those who collected the most emails. Our patient portals and federal Meaningful Use standards are also helping with collection.

DID YOU HAVE PUSHBACK ON RESPONSE RATES AND N-SIZES?

Yes, response rate is important. We believe a minimum of 30 survey responses per physician is necessary to draw meaningful conclusions from the data. Moving from paper to email surveys yielded a fivefold increase in our return rate.

DID YOU NOTICE A DRAMATIC INCREASE IN INTEREST IN HIGH-SCORING PROVIDERS OR DECREASE IN LOW-SCORING PROVIDERS?

This might be happening but we haven’t measured it directly, and we haven’t seen a revenue or patient-volume decline in any of our units. That’s partly because we’ve focused on improving access across the board, which has led to more patients entering our system.

HOW DO YOU REWARD OR RECOGNIZE HIGH-PERFORMERS?

We have a “no carrots, no sticks” approach re: financial incentives. But we make quarterly rounds to celebrate units that are exceeding goals in quality, patient satisfaction and efficiency. We also give lapel pins to our top 1 percent and publish newspaper ads congratulating them and their units.

WHO CAN I CONTACT TO LEARN MORE?

Chrissy Daniels at chrissy.daniels@hsc.utah.edu