CAN WE LOOSEN OUR GRIP WITHOUT LOSING CONTROL?

There's a lot of uncertainty swirling in health care, sending stakeholders retreating to their corners or looking for safety in numbers. Change all too often seems like a zero-sum game. Someone comes out the winner, and someone comes out the loser. So we hang onto what we know, believing that loosening our grip means surrendering all control. But do we have more to lose than gain from hanging so tightly to the status quo?

Every year, hospitals and insurers come together to negotiate their rates. “We call it the scrum,” says Chad Westover, M.P.A., CEO of University of Utah Health Plans. Like in rugby, the two sides collide, muscling for control of the proverbial ball, and either the hospital or the payer comes out better. But what happens to the consumer in that equation?

A similar scrum often plays out between independent-minded providers and tightly structured health systems. Those are the rules of the game, we tell ourselves, while the true losers are those relegated to the sidelines—consumers and the American economy. Health care spending has resumed its upward climb, reaching $3.1 trillion last year, or $9,700 per person. By 2042, if we continue on the current trajectory, it’s estimated that out-of-pocket health spending will consume 100 percent of the average household’s income. “At some point payers and providers have to realize it’s not just about them,” says Westover, who has played on both sides of the field. “If we as a health system don’t address the issues of value, cost, quality and access, then someone else will.”

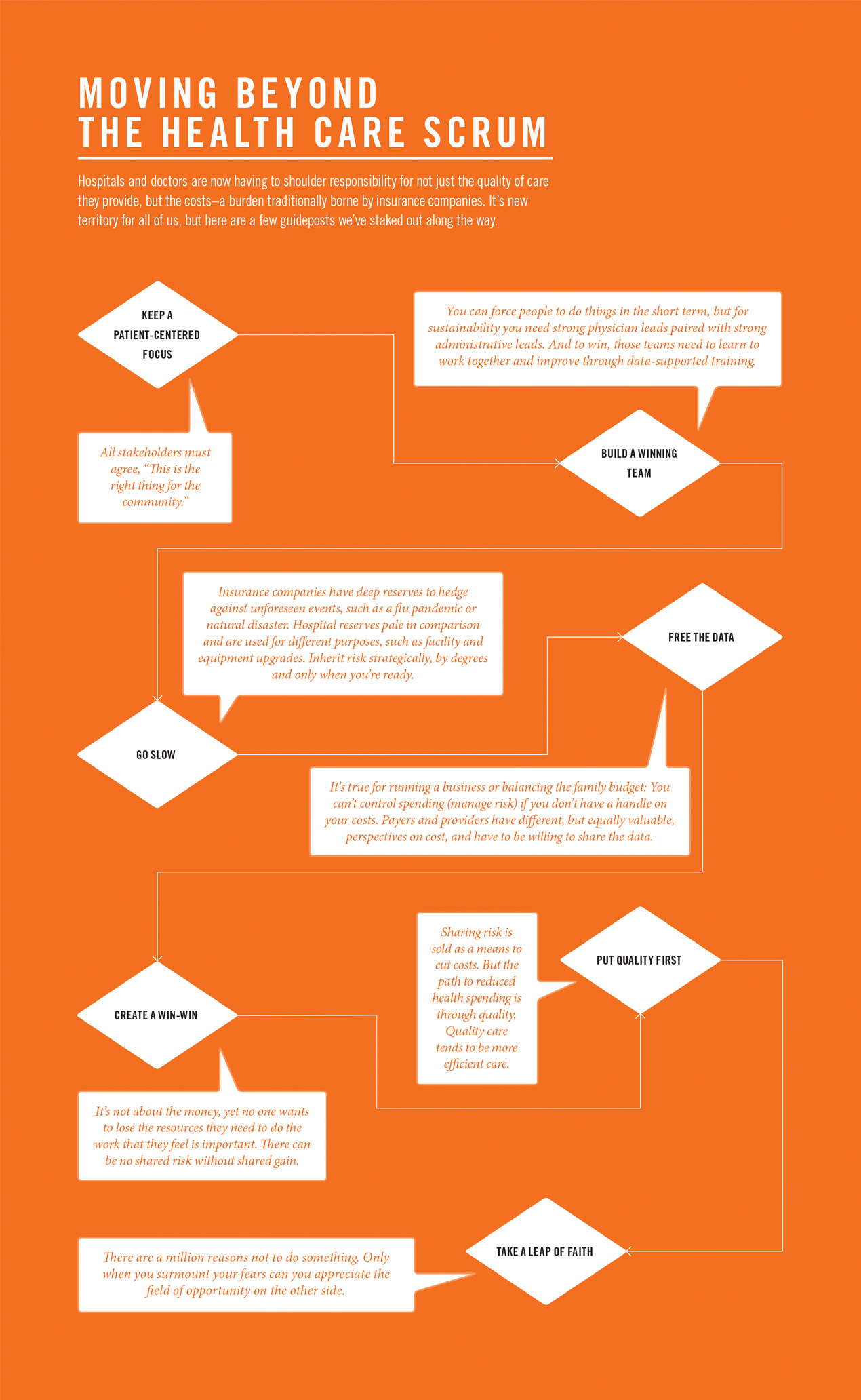

Predicting the future of health care is like imagining the iPhone 10, says Westover. But he and many others are confident that aligning incentives and integrating payers and providers through new partnerships will help shape it. These are uneasy and unfamiliar unions, demanding unprecedented levels of cooperation, mutual respect and trust—and requiring individuals and institutions to get beyond the idea that giving up some control is a slippery slope to full surrender. “We can make great progress if we let go of the fear that we’re somehow going to come out worse, and instead ask, ‘What’s the need of the patient? What are the needs of the population? And are we organized in a way to take care of them?’” says Sean Mulvihill, M.D., CEO of University of Utah Medical Group.

Chasing Unicorns

The hope is that all of us jointly accepting accountability for the quality and cost of care will make health care better and more affordable. If there’s a gold standard for doing this, it’s the Accountable Care Organization (ACO), which has famously been compared to a unicorn: A fantastic creature vested with mythical powers that no one has actually seen. This may have been true in 2010 when the idea was enshrined in President Obama’s signature health reform law. But now, there are hundreds of public and private ACOs. The idea of payers and providers working as allies to share in the equity of what they build together isn’t novel for some organizations. But for academic medical centers, it’s new territory. “Right now, we’re focused on providing care, doing research and teaching students. Soon we will be partnered with health plans,” says David Entwistle, M.H.A., CEO of University of Utah Hospitals and Clinics. “It’s really sparking conversations about doing things in completely new ways.”

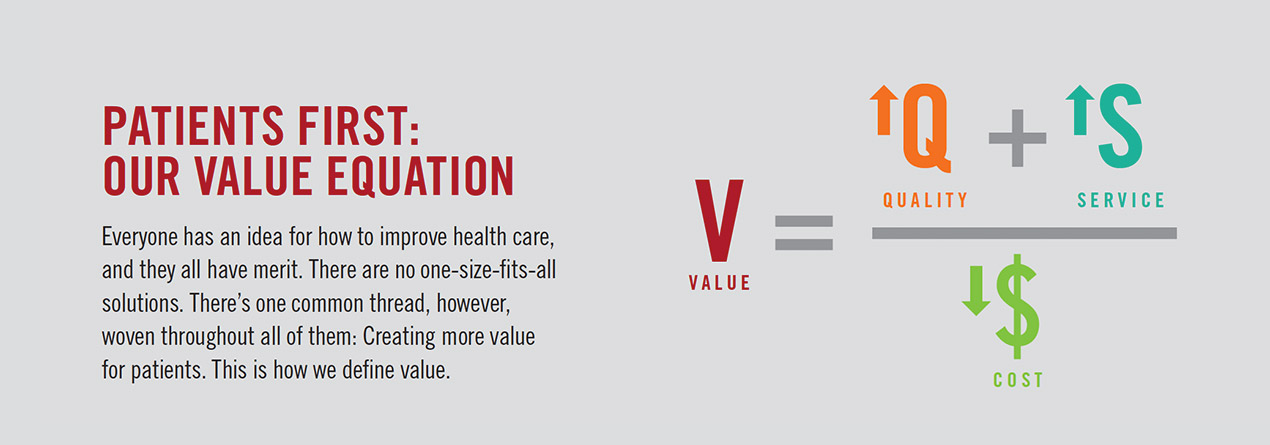

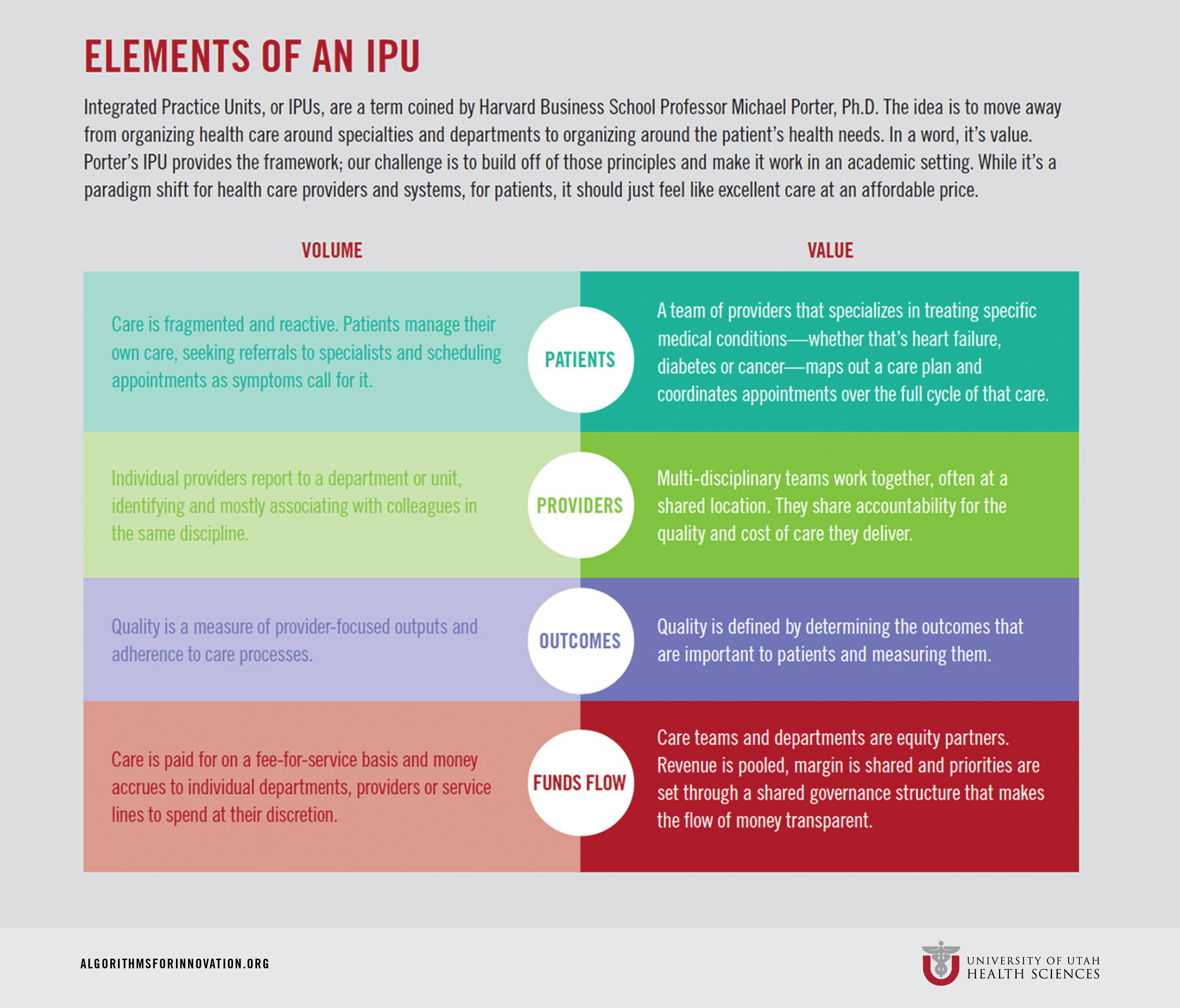

While it often seems that these conversations focus on the business of health care, at the end of the day, it’s not about the money, says CFO David Browdy, M.B.A. “Money is in the way right now. The goal of these partnerships is to get money out of the way of redesigning care. It’s about delivering greater value to patients.” We’ve had a lot of “magic bullets” that don’t get at the real problem, which is the fundamental structure of health care delivery, said Harvard Business School Professor Michael Porter, Ph.D., on a recent visit to the University of Utah. “We’ve got to transform the actual way we deliver care. How you work, how you measure what you’re doing and how you define success. And we need absolute clarity about what our fundamental purpose is: delivering value to the patient.”

Porter’s recipe for bringing harmony to the cacophony of competing interests and misaligned incentives is the Integrated Practice Unit (IPU). That is, moving away from organizing health care around specialties and departments to organizing it around the patient’s problems and measuring success based on outcomes. He agrees that how we’re reimbursed for delivering this kind of coordinated care needs to change, but urges health systems not to wait around for payment reform. “Take a hard, honest look at where you are as an organization,” Porter said to health care leaders at a recent conference. “Start with your goal and then ask: Where are you making progress? Where haven’t you started?”

Better Together

There are 100 things that have to happen between having an idea and implementing it, not the least of which is convincing people that change is good. “There’s so much pressure for organizations to move quickly, make decisions and be agile in today’s world, that we often forget to involve and bring people along,” says Health Sciences Chief Counsel Elizabeth Winter, J.D., B.S.N. “Sometimes we need to slow down and acknowledge people for making countless little steps on the way to realizing big ideas.”

Big system changes prompt big concerns, says Sonja Van Hala, M.D., M.P.H., associate professor of family and preventive medicine, such as: “Will I be asked to sacrifice the autonomy or resources I need to do the work I feel is important?” Even smaller changes can be unsettling. Van Hala gives the example of when she learned that her clinic would be extending hours and expanding from two shifts a day to three. Understanding “the why” is key to adapting, followed by, “How is this going to affect my life?” When you don’t know answers to these questions, you can become defensive about maintaining the status quo, she says. But when you understand the reasons behind them (greater access for patients in this case) you open up and sometimes even gain more than you lose. Now, on Mondays Van Hala often doesn’t finish clinic until 9 or 10 p.m. But her later shift has opened up new flexibility in her schedule, allowing her to play tennis every Monday morning. By taking care of her own wellness, she is more resilient and engaged in her work. Moreover, she says, there’s a sense of satisfaction that comes with telling patients they can come see you tonight and that they don’t have to miss work to do so. “Patients express gratitude, and we take pride in that,” says Van Hala, who has some of the highest patient satisfaction ratings in the entire system. “It feels good.”

Feeling Valued

Although "value" in health care is associated with better outcomes at lower cost, the word is rife with meaning. When people feel personally valued-both by their patients and by the administration-they're much more willing to talk about the "value proposition," says Dan Lundergan, M.H.A., who has worked at the University for 40 years and is now the executive director of Services Lines, Specialty Clinics and Support Services. "Change is visceral," says Lundergan. "If as a system we're not taking care of people's hierarchy of needs, they may not be in a place to move to a different level."

For Chair of Pediatrics Edward Clark, M.D., inspiring people to let go and change comes down to thoughtful leadership. "Leadership isn't management. It's understanding the social dynamics of a group and how to change the culture of that group," says Clark. "The two most frequent and powerful questions I can ask are: What would you like and what are you afraid of?" By asking those questions and listening to the answers, Clark believes, we can prepare the organization for the future.

The solutions are not out of reach, says Kristen Keefe, Ph.D., interim dean of the College of Pharmacy. “We need to set aside time to allow ourselves to get off this treadmill long enough to think of the most creative solutions—to think deeply and broadly. And then to have the courage to make those changes now.”

Case Study No. 1

An Exercise in Trust

Sharing risk is scary, and requires a lot of trust, especially between two financially separate organizations that happen to be competitors. So it’s perhaps not surprising that the idea of creating an Accountable Care Organization (ACO) with Intermountain Healthcare-owned Primary Children’s Hospital; its physicians, most of whom are University of Utah faculty members; and Intermountain’s insurance arm, SelectHealth, left a few people scratching their heads. Grant Lasson, M.B.A, associate vice president for strategy, half-jokingly responded. “It’s a great idea. The only thing we can’t figure out is, what’s in it for us?”

To Clark, who straddles both institutions as chair of pediatrics and chief medical officer of the children’s hospital, the answer was clear. “What’s in it for us? Aligning incentives around delivering more efficient care.” By way of example, Clark points out that providers had been successful in eliminating wasteful tests, treatments and spending—in some departments by more than 30 percent. Children were spared poking and prodding, and families and insurance plans enjoyed the cost savings. But these efforts translated to lost revenue for the hospital and providers. In other words, they were financially penalized for providing better care. “We needed to create a more sustainable solution,” says Clark.

Doing the Right Thing

The idea behind an ACO is to align financial incentives around doing what’s right for patients. Pediatric Specialty Services (PSS) was designed to be that, an opportunity for everyone to dip their toes into ACO waters while still firmly planted on fee-for-service ground. In this case, the payer agreed to give a certain amount of money to care for a defined population of children. The hospital and providers agreed to pool their revenue and jointly bear financial risk for those patients. If they run out of money, they share equally in the loss. Conversely, if at the end of the year they have a margin, they share equally in the savings.

It wasn’t easy coaxing harmony from all the players. “There were a lot of times where it felt like we were going back to baseline,” says Primary Children’s Hospital CEO Katy Welkie, R.N., M.B.A. It took at least a year of telling the story and would have probably taken much longer without the buy-in of top leadership, Welkie says. “The organizations had to agree, ‘Even though we’re competing entities in other places, in pediatrics, this is the right thing for the community.’”

To govern the ACO, the hospital and doctors started by developing a consensus-building board equally weighted with leaders from Intermountain and the University. The stockpile of trust that the two institutions had built over the years proved to be critical in the early stages, and later, when it came time for letting go of closely held financial and outcomes data. Division Chief of Pediatric Emergency Medicine Howard Kadish, M.D., M.B.A., who co-administers the ACO from the University side says, “I’ve been on the pediatrics faculty since 1992, and the only place I’ve worked clinically is at Primary Children’s. We all know and trust one another.”

Shared Risk, Shared Gain

A prior investment by both health systems in robust data warehouses was also essential. “We know our costs, right down to supplies used in surgery, which is something that eludes most health systems,” Kadish says. “You can’t do this without sharing detailed data on costs and things like average length of hospital stays for different diseases processes.” Strict criteria dictate who is allowed access to what information in compliance with federal privacy and antitrust laws.

Then there was the matter of fairness. “In most ACOs, hospitals take a larger share, but we agreed to an even split,” says Kadish’s administrative partner from Intermountain, Seth Andrews, M.B.A. “We were very conscious that the financial risk for physicians was greater than for the hospital, which has the support and resources of a large health chain to fall back upon.”

What really sets PSS apart from other risk-sharing agreements is its limited design. Because the goal of ACOs is to keep patients healthy and out of the hospital, they generally focus on managing all of their health care needs. But Primary Children’s is an acute-care facility drawing patients from five neighboring states. “We looked at our market and we didn’t think it made sense for us to get into primary care,” says Andrews. Instead, the group defined a realistic scope of services for which they’d be responsible: Specialized outpatient and inpatient care, from appendectomies and pneumonia to transplants and childhood cancer. “We said, ‘here’s a population of kids who cost this much, and we’ll take total risk for their specialty services, but no more.’”

A Leap of Faith

Now just 10 percent of Primary Children’s patients fall under ACO, which went live in January 2015. The goal is to bring two-thirds of the hospital’s patients into the mix. It’s too early to make predictions, but six months into the pilot, providers are on track to come in under budget.

What’s in it for the payer? Predictability. Usually the payer has a sense based on historical data of what its claims might be in a year. But in this arrangement, SelectHealth knows upfront exactly what it will pay in claims for those conditions, enabling it to set premiums more accurately. The hospital and physicians win because they are free to focus on delivering the most coordinated, patient-centered care without being restricted to services reimbursable by insurance. Take the example of kidney disease and recurrent urinary tract infections, says Patrick Cartwright, M.D., chief of urology and surgeon-in-chief at Primary Children’s Hospital. “Our standard approach is to have these patients visit us on a regular schedule. But maybe what creates the best outcome is to have a nurse visit them every two weeks, helping them manage problems at home.”

Money saved through such projects can now fuel a quality improvement pipeline. “This is like an internal granting system,” says Cartwright, describing a Value Enhancement Quality Assurance committee set up to review proposals. The committee uses data to model the potential of different ideas and prioritize those projects with the greatest impact.

It took a leap of faith, but now there’s a general feeling of excitement, Cartwright says. “When the pay schedule completely changes, people worry that someone will take advantage. But with PSS, there’s so much opportunity I think most of us realized we would be foolish, even cowardly, to not take the risk.”

Case Study No. 2

Birth of an 'IPU'

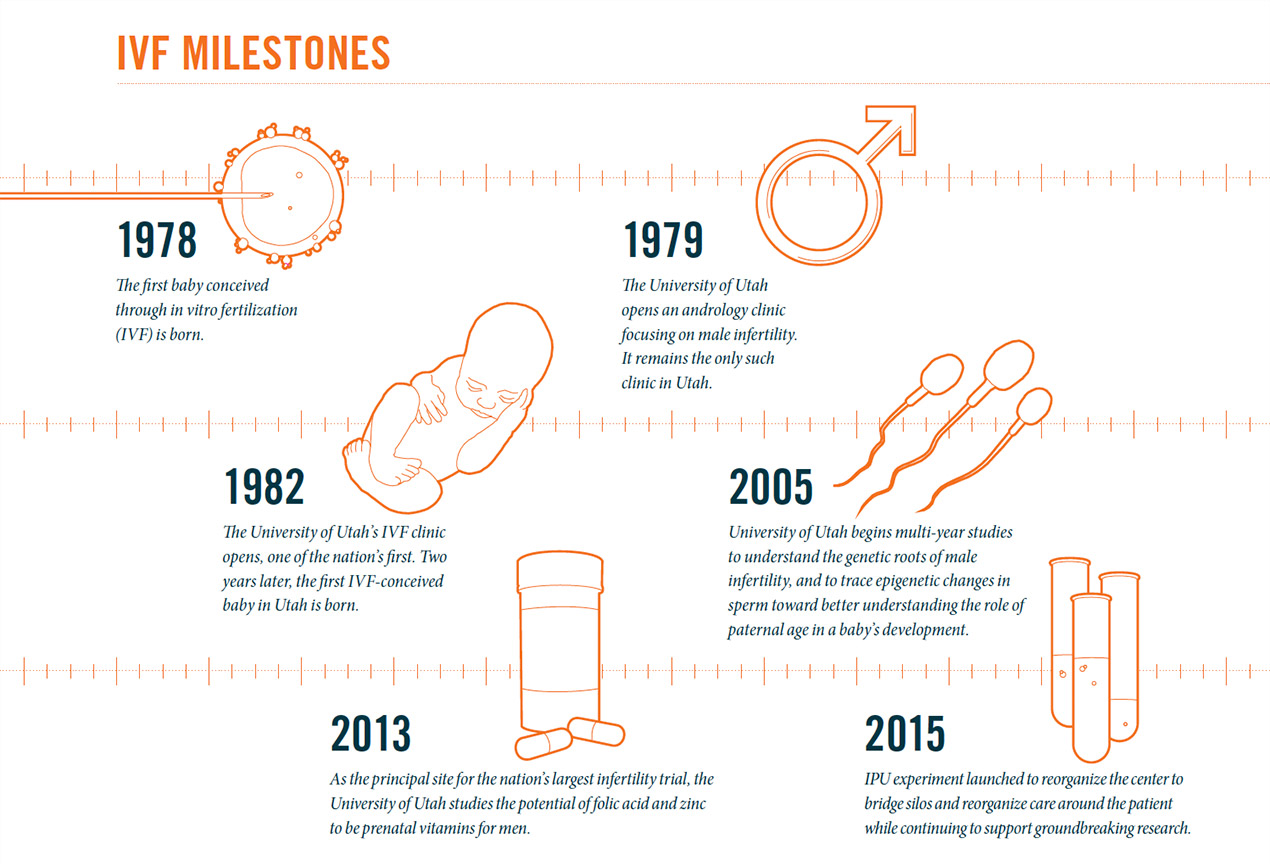

Hopeful couples come to the University of Utah’s Center for Reproductive Medicine with a singular goal: To get pregnant. It’s an emotional experience. They pay cash and hope desperately for a good outcome. And for many years the center has exceeded their expectations with some of the highest in vitro fertilization (IVF) success rates and lowest costs. Still, behind the scenes staff knew that care wasn’t as streamlined as it should be.

Women were cared for by the obstetrics and gynecology department, men were seen by an andrologist in the surgery department and their eggs and sperm hooked up in a petri dish in a separate lab. “Staff and faculty reported up to two different departments, so everything had to be filtered through the leadership structure, which is not the most efficient way of getting stuff done and a little bit of a game of telephone,” says Erica Johnstone, M.D., M.H.S., assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology. To compensate, the care team developed workarounds that ultimately contributed to breakdowns in communication and patient flow. “I’d have a patient in my office, and because I didn’t have the lab results, I couldn’t tell her that we had viable embryos and she might soon be pregnant,” says Johnstone. Even technology couldn’t bridge the rift: There’s currently no way to link a man and a woman in the electronic health record.

The Academic Labyrinth

If health care is complicated, academic medicine, with its tripartite mission, can become labyrinthine. So many of the ways we’ve organized ourselves and the funding streams that support us seem haphazard, but serve an organizational purpose. At the same time, it sometimes prevents us from providing the most patient-centered care. How can we bridge silos to improve care and still do groundbreaking research? Our Center for Reproductive Medicine, one of the few areas in health care where “the patient” is an entire family, seemed a great test case to find out.

“This was the perfect opportunity to look at the imperfect way we’ve organized ourselves as a health system,” says Senior Vice President Vivian Lee, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A. Lee issued a mandate to find a better way and suggested the vehicle: An Integrated Practice Unit (IPU). Foundational to an IPU is organizing care around the patient and making everyone involved accountable for the full cycle of care and overall outcomes, not just for their limited role. “We’re climbing a big hill of 100 years or more of a system that’s been provider focused. How do you turn a culture?” says Grant Lasson, M.B.A., associate vice president for strategy. Departments with a stake in the proposed IPU are still ironing out the governance structure, how to pool revenue and the much more difficult task of how to reallocate margin. That is no small thing. “These are some of the hardest conversations we’ve had,” admits Lasson. “But I’m confident that what we figure out here will create the model and inspiration, not just internally but for other systems as well.”

At the heart of many of these conversations is a philosophical question. IVF clinics are incredibly competitive and price sensitive. Payment is already bundled. The imperative to deliver greater value—quality, cost and service—is clear. So where does research fit into the value equation?

Truth is, once there’s a treatment for a condition, there’s much less interest in finding out the root cause. IVF is itself a very successful workaround for infertility. The University has persisted in research to uncover the underlying causes—focusing on male infertility and how the sperm contributes to embryo quality. “In many ways, the Y chromosome has been along for the ride,” says James Hotaling, M.D., M.S., assistant professor of urology. The University has one of the top labs, if not the top lab, in the genetics of male infertility. Overseen by Douglas Carrell, Ph.D., professor of surgery, it boasts the largest biobank in North America, two NIH-funded RO1 grants and a clinical trial. The researchers, all based in the surgery department, have linked 40,000 infertile couples to the Utah Population Database, a repository of clinical data matched with genealogical records. “This is critical knowledge for parents to understand their pregnancy challenges and risks,” says Hotaling. In addition, they’re looking at the long-term health outcomes of children conceived through IVF. “Because people have kids so young in Utah, we predict we will be able to follow 170 grandkids of people who did IVF.”

But that cutting-edge research comes at a price. Historically it has relied heavily on funding generated by the center and the embryology lab, also based in surgery. “We’re faced with how we remain competitive in a highly price-sensitive and price-transparent market and continue our research,” Hotaling says. That’s the journey we’re on, creating a financial model that makes sense for our patients and clearly defines who we are as an academic institution.

A Tectonic Shift

An interesting thing has happened along the way to creating an IPU. The mere idea of integrating the team and aligning care around patients is sparking different conversations and bringing people together for the first time to examine care processes. “These are people who have worked together for years but never had casual conversations with each other,” says Johnstone, who has worked with Hotaling to bring the center’s staff together for “brown bag” lunches. “No one is shocked by the problems we find, or by the fact that it’s convoluted. But until now, we haven’t had a complete view of the system.”

These open conversations are re-energizing staff. Using lean management tools and working with process engineers, the team is identifying countless opportunities to improve clinic flow. They’ve hired new medical assistants and a dedicated sonographer to better coordinate care and open up capacity. “You get the best performance from people when they feel empowered to make change,” says Johnstone. “Nobody before now, including me, felt empowered to make change. We didn’t even have a pathway to manage change.” Hotaling agrees: “This has been a tectonic cultural shift. We’ve already shifted 180 degrees.”

Over the past three months, patient satisfaction scores have risen 38 percent, driven primarily by reduced wait times, improved communication and ease of scheduling. It’s not clear how much to credit the proposed IPU when other improvement efforts could be influencing the scores, though Johnstone is confident it has helped. With greater transparency of finances, it’s easier to prioritize purchasing decisions and agree to shared goals. Lab manager Benjamin Emery, M.Phil., describes it this way: “It’s just a temperature change overall with the staff. It feels like this weight that was pressing down as things got more complicated is now lifting. Spring is here, and that’s a really good place to be. We hope summer is on the horizon.”