OutcomesWho's Responsible?

The path to a good outcome is hardly straightforward. Anywhere along the way, systems and behaviors can advance patients forward or set them back. Government metrics tried to ensure safe passage, but 1,700 checklist boxes later, no one is satisfied. Patients and providers are starting to take matters into their own hands and hold each other accountable.

You won’t hear William Couldwell, M.D., Ph.D., utter the phrase, “It’s not brain surgery,” because most of the time it is. Chair of the Department of Neurosurgery, Couldwell travels the world training other neurosurgeons and spending as many as 12 hours in the operating room working against the odds of a ruptured aneurysm or teasing out tumors that tangle dangerously close to critical brain tissue.

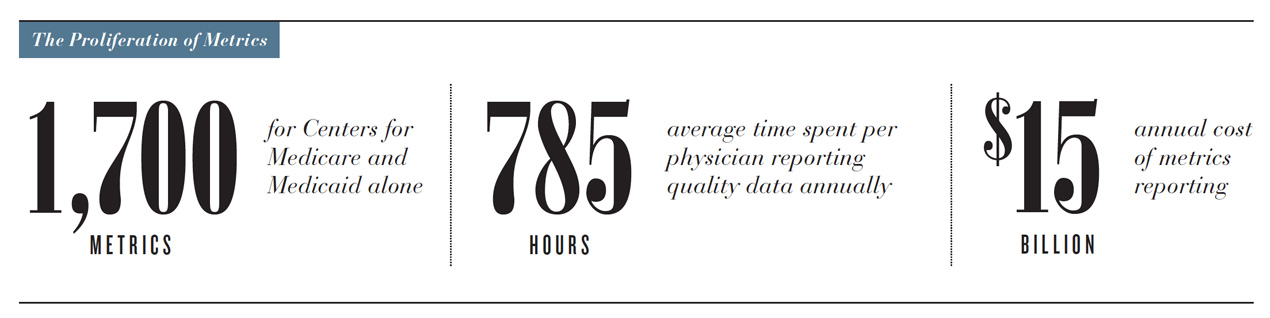

When one of his patients wakes up from surgery and takes perhaps the most grateful breath of her life, she next wants to know “Can I still see?” “Can I hear?” “Do I recognize the person sitting at the side of my bed?” But those are not the metrics that will measure Couldwell’s performance. Instead, 15 years of education and training and 30 years of experience will be measured by a cascade of hospital, government and insurance company metrics—from the routine (quick administration of antibiotics and catheter removal) to the practical (the speed with which the patient is up on her feet and sent home or to a skilled nursing facility). Doctors, residents and nurses will check off hundreds of boxes pre- and post-surgery that will be used for rankings, accreditation, reimbursement and, in some cases, nothing at all.

What they won’t measure, at least not yet, is what’s really important: the improvement in a patient’s quality of life, his ability to go back to work or her joy at being alive to see a child married or a grandchild born. “We take away the threat to a patient’s life or extend someone’s life,” says Couldwell, “but none of these metrics asks questions that would capture that.”

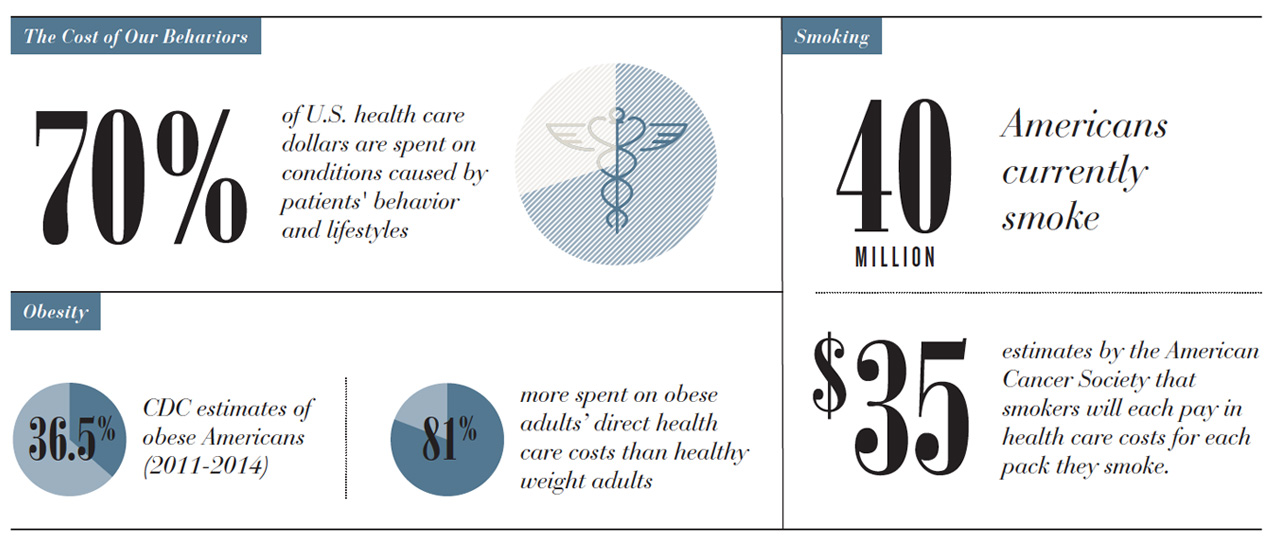

At the same time, metrics have improved medical outcomes, cut costs and saved lives. We’ve needed some way to justify, quantify, measure and control what we’re doing, especially in light of the Institute of Medicine’s estimate that roughly 30 percent of U.S. health care spending is squandered on unnecessary, poorly delivered or wasteful care. For the most part, the federal government has taken on that responsibility, creating more than 1,700 quality and safety metrics.

The problem is that metrics are designed to simplify, but health is incredibly complex. How a person feels, ultimately, cannot be measured by adherence to processes. It’s deeply personal and variable. The other problem is that, like so many patriarchal traditions in medicine, providers, systems, government and payers have all taken a we-know-best approach and left out one important voice—presumably, the very person to whom the outcome matters most—the patient. But that’s changing.

Inviting The Patient In

Three years ago, Marge Torina was working in her yard, scraping a pile of leaves out from under the porch. It might have been the flip-flops. It could have been the tools, or both. But she tripped. And whatever the cause of her fall, Torina couldn’t get up. She scooted across the dirt, yelling to catch the attention of a dog walker nearby who called an ambulance. She had shattered her hip and ended up with a 17-inch rod in her leg.

For Italian grandmother Marge Torina, her goal was to stand in the kitchen long enough to make “summer pasta” every year for her children and grandchildren.

For superbike racer Shane Turpin, his goal was to get back on his bike, even after some doctors told him he would never walk again. “This is who I am,” he says.

When she transferred to University of Utah Health’s Rehabilitation Center, rather than starting with a standardized program, her therapist asked about her life and her goals for recovery. The team then created a regimen tailored for an Italian matriarch who wanted, more than anything, to be able to cook Sunday dinner for her family. Instead of putting her on the stationary bike, the therapists took her grocery shopping with a group of patients and then put her somewhere she loved—the kitchen. She spent the next couple of hours making her signature summer pasta, a celebration of hot-weather bounty—vine-ripened tomatoes, black olives, onion, basil and “lots of cheese”—and proudly served it up to hungry staff. The next therapy session, she made pizzelles, delicate anise-flavored holiday cookies. Three years and countless Sunday dinners later, 80-year-old Torina remembers her rehabilitation with fondness. “It was fun,” she says. “It was better than going down there and doing exercises. And it was a lot of training for when I did eventually get home.”

“Patients find motivation and hope when thinking about being able to do the things that bring joy to their lives,” says Occupational Therapist Christopher Noren. “So that’s what we focus on. Rather than routine exercise and set programs, we try to tap into intrinsic motivation and the things that matter most to each individual.”

"Rather than routine exercise and set programs, we try to tap into intrinsic motivation and the things that matter most to each individual.”

Occupational Therapist Christopher NorenFor professional superbike racer Shane Turpin, that was getting back on his bike. The 49-year-old had taken the weekend off to ride dirt bikes with friends when he shorted a jump and landed awkwardly. He managed to save the landing but he could feel bones moving in his boots. He’d broken the tibia and fibula in both legs. His ankles were shattered.

The first doctors he saw gave him grim news: He would never walk or compete again. Three hospitals later, he ended up at U of U Health. With amputation the only other option, Turpin wanted surgery immediately. “I didn’t care about the consequences, I just needed my legs.”

After five operations—and two months of intense, home-based rehab involving a training bike on rollers—Turpin hit the track and set the fastest lap of the day. “I’m not 100 percent. But I’m close. I’m going faster than I ever have, and I’m almost 50.”

Finding The Sweet Spot

“Every day we’re trying to figure out what a patient wants to do, what the provider can do for them, and if there’s a match,” says Charles Saltzman, M.D., chair of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery. Consider the options for a 60-year-old patient with end-stage arthritis: the surgeon could fuse the ankle and the patient’s pain would abate, but he would have a hard time walking up and down hills. Replacing the ankle would provide better function, but limit high-impact exercise. “Finding out what the patient’s goals and expectations are is a critical part of being a good doctor,” says Saltzman

As a health care system, Saltzman admits, we haven’t been very good at asking patients what they want or sorting out how well they function before or after treatment. So in 2009, he started doing just that. The Department of Orthopaedics launched an early version of the NIH’s Patient- Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), and then worked with a U of U Health team to create a customized, patient-friendly tool called mEVAL Personal Health Assessment. Patients can fill out an online assessment before their appointments or complete a brief computer adaptive questionnaire on an iPad when they get to the clinic. Questions range from their level of pain and social support to whether they have feelings of depression and anxiety. These patient-reported outcomes (PROs) provide physicians with critical information that can be used at the point of care, says Saltzman, especially when dealing with a patient who isn’t a good communicator. They also help track progress over time and help the clinician and patient understand if that progress is appropriate based on data collected on other patients with similar problems.

Today in 30 clinic waiting rooms at U of U Health, patients are tapping on iPads before their appointments, reporting on their functional, psychological and pain status. The number of patients completing the questionnaires has doubled to nearly 13,000 per month. And by the end of 2018, PROs, including pre-visit emails and mid- and post-treatment questionnaires, will be used throughout the system. Not only will the information guide patient-physician discussions and help providers individualize treatment, it will also provide a resource for researchers to look more broadly at outcomes.

“We finally have a systematic way to listen to our patients,” says Senior Vice President for Health Sciences Vivian S. Lee, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A. “That gives us the opportunity to marry that information with our expertise to personalize their care and, ultimately, to begin measuring outcomes in terms of what is important to patients.”

Shifting Responsibility, Just a Little

Thomas Varghese, M.D., M.S., associate professor of thoracic surgery, makes his expectations clear from the first consultation with a lung cancer patient: Stop smoking or find another surgeon. With his Surgery Strive program, modeled after the Strong for Surgery program he helped found at the University of Washington, Varghese has his patients sign a contract of sorts, agreeing to make the lifestyle changes necessary to improve their surgery outcomes. He’ll refer you to the wellness clinic to get your blood sugar in check. And he’ll help you quit smoking— provide you with nicotine patches, write a prescription for Chantix or sign you up for a cessation program. But he will not operate on you if you’re smoking. A simple blood test will show if you’re lying.

It’s not as paternalistic or heartless as it sounds. For years, doctors cajoled and urged their patients to exercise and quit smoking. But changing patient behavior is more a lifelong campaign than a pre-surgery project. “Patients are adults,” says Varghese. “It’s about having hard conversations and sharing in the decision-making.”

Varghese knows some of his patients may sign under duress and others will look for another surgeon. But eventually, he figures, all surgeons will be holding patients accountable in the same way. He may be right. This year, the American College of Surgeons adopted the pre-surgery checklists as standard procedure. Britain’s National Health Service took it a step further. In September, it announced it would block obese patients with BMIs over 30 and smokers from most surgeries—including routine hip and knee operations.

Partnerships and Mind Shifts

“Transitions are a time when patients are really vulnerable for complications and readmissions.”

Carole Baraldi, M.D. Associate Professor (Clinical) of GeriatricsOf course, measuring a successful outcome for a hip replacement, a round of chemotherapy or a baby’s birth is much easier than defining a good medical result for chronic conditions. “For years, we’ve been stuck in a plumber model of health care,” says Sam Finlayson, M.D., M.P.H., chair of surgery. “Fixing the faucet when it blows generates a lot of revenue but doesn’t necessarily make patients better long term. Reversing a long, slow, recurring ‘leak’—like diabetes or heart failure—or preventing it in the first place, is a much more difficult thing to incentivize.” Care for patients with chronic conditions—many of them elderly—can be particularly fragmented with multiple specialists and no one held responsible for the overall health of the patient.

After surgery, Keith McDonald was given a complicated discharge plan that he and his wife were preparing to do from home—130 miles away. Instead, under a new post-acute care model, the McDonalds checked into Brookdale Senior Living in Salt Lake City. “We’ve known that transitions—especially for older adults—are a time when they’re really vulnerable for complications and readmissions,” says McDonald’s doctor, Carole Baraldi, M.D., associate professor (clinical) of geriatrics. Now we’re taking responsibility for patients’ long-term care— and overall health—by partnering with these skilled nursing facilities. “Our goal is to have patients leave us healthier than when they came in.”

“As we begin to move away from the old fee-for-service model, providers will become heavily accountable for patients’ overall health, not just the outcome of a specific surgery or illness,” says Mark Supiano, M.D., director of the University of Utah’s Center on Aging. “Taking on that responsibility will require a reset in the way that many physicians and systems think.” It also will force systems to form new partnerships across the continuum of care. Working with an interdisciplinary team, Supiano’s created a new “medical home” designed to break down the physical and technological barriers that plague communication between hospitalists, post-acute care centers and primary care physicians.

A new way of thinking

With new payment models and shifting responsibility for outcomes, we have to relearn how to talk to each other. Finlayson calls it the “dialectic” between providers and patients, a shared responsibility for the way we work together to maximize medical outcomes.

Others agree. “We tend to throw the onus on the other party, but we need to recognize that patients often don’t have the resources—intellectually, emotionally or financially—to align their lives to what their medical care team is trying to educate them to do,” says Nate Gladwell, R.N., M.H.A., director of telehealth for U of U Health. “We can prescribe, we can educate, we can diagnose all we want. But at the end of the day, health care is a partnership,” he says. “It’s going to take all of us.”